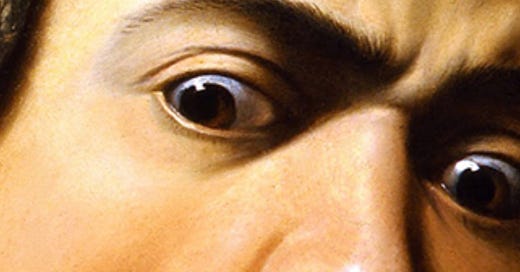

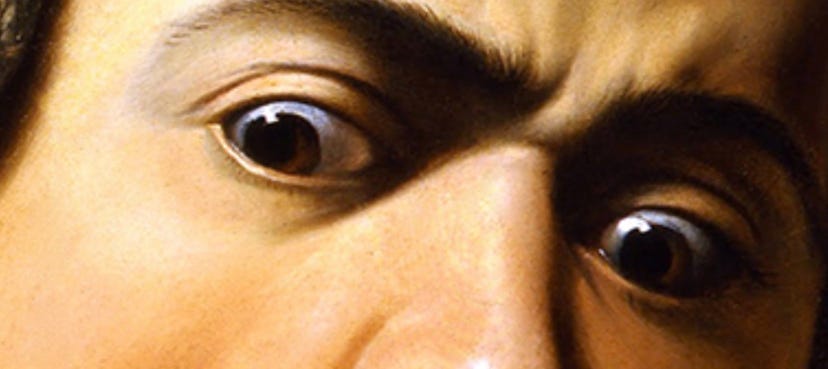

Detail of Caravaggio’s Medusa

How should I describe the mixed satisfaction of finding a book by someone who shares your ideas on a condition widely manifested in modern society, but then takes his observations regarding a cure in a direction you have sad misgivings about? The book I am referring to is Andy Crouch's The Life We're Looking For: Reclaiming Relationship in a Technological World. The idea that is not at issue is what I defined some three years ago as 'mental obesity': our negativity bias that had great value in evolutionary terms, but once our wellbeing reached a - truly incredible - level of security, seems to induce us to hystericize non-existential issues. I pointed out that technology has stimulated a magical relationship with reality, symbolized by the wielding of the remote control that exerts control over our surroundings in an invisible, indeed magical, manner, leading to a similar expectation when we encounter different circumstances and another tool to wield. Underlying this spell is the fact that for any tool available, increasingly few have an actual understanding of its actual functioning. The example that always comes to my mind is the ritual opening of the hood when our car breaks down. How many of us do that without any reasonable expectation of even approximately identifying the technical issue? And I would add that without a mind constantly looking for meaning and agency, all of this would not be much of a problem. I consider God and gods a projection of this characteristic of our mind on the wider world, and to return to the above book and the contrast I anticipated, Crouch believes this relationship is its contrary.

What I find wonderful about Crouch's book is the fact that he shows - in my opinion convincingly - how technology has spiritually impoverished us. It tempts us to neglect and abandon a series of our inner functions that - at least formerly - made us who we are. Not needing to memorize makes us forget. Not moving around makes us fat. Not needing to reflect makes us stupid. I am tempted to describe this development as our devolvement into the "survival of the unfittest". Crouch links this attitude towards technology with the practice of alchemy. Under the spell of the dream of subjecting reality to the reach of our magical powers, we started abandoning our wholeness - consisting, in his words, of "heart, soul, mind, strength" - and catered to our fantasy of "effortless power".

Crouch starts his book appealingly with a representation of how we are born: seeking recognition. It is modern technology - our wonderful devices - that has severely damaged this most basic ingredient of relationships. This is not merely due to 'social' media replacing the direct contacts we all used to maintain, not based on algorithmically defined shared clicking patterns. It is inherent to our recourse to devices to keep children quiet and engaged. It is part and parcel to the outsourcing of our most intimate searches to dating sites. And according to Crouch - and this is where I nevertheless came to be disappointed with his book - this development is the result to our fealty to an empire that is not new, but possibly more dominant than ever: Mammon. Yes, just money was not enough. The attraction it exerts on us, he says, is in a mode parallel to our dream of "effortless power" - because it encapsulates "abundance without dependence". My disappointment at this twist in Crouch's narrative derives primarily from the fact that the m-word - in either version - is a bit of a platitude.

Early Christianity (which he uses as the counterpoint to our depraved, current ways) of course was presented as a departure from the material covetousness that is only such an effective boogeyman because it is such a universal, natural instinct. Where Crouch points out that Christianity would eventually replace a (Roman) society that was thoroughly violent, I would insist to observe that - some rare romanticizing aside - the society that resulted was hardly ideal by any standard. The Middle Ages were a prolonged period of famine, ignorance, more violence (even if not at the Colosseum), religious prosecution, poverty, the collapse of learning (of any subject besides the Bible - while we somewhat ironically owe the survival of seminal texts of 'our own' Classical Age to the Muslim world). And "abundance without dependence" may, indeed, sound as terribly conceited, but how many people have been able to escape abusive locations and relationships thanks to the liberating power of financial independence? As a matter of fact, until totalitarian policies of the 'rona era placed a dramatic hold on this development, fewer and fewer people were actually living in poverty throughout the world. For the simple reason that they were finally able to fend for themselves and eke out an honest and decent living in the sweat of their brow.

What empire is actually taking over the reins of control over our lives, as we stare in addicted obsession at our screens? Crouch dedicates a charming chapter to a discussion of the type of tool that does not empty us: the instrument. It can be a telescope or a guitar, a pair of scissors, or a bicycle. These are the tools that allow us to be even more of ourselves. Does the emptying of our internal faculties into the devices not amount to the reduction of ourselves to the not-so-glorious status of instruments? Where we are waiting to have our buttons pushed, our momentary furor recruited, and our lives mortgaged for the next crusade? The institutions of unaccountable global control, and their ruling caste of an unelected clergy of technocracy have gotten hoards of us under their control already. This class, so ready to rule, promises to give new meaning to our lives, scaring us into obedience with story after story of the imminent end-of-times. It does sound familiar, indeed. As does the projection inherent in it: our fantasy to be the center of the universe, ready for penance, eager for the next orgy of self-obliterating, bloody violence. One point I have to concede to Andy Crouch, of course. Those who believe in God have a well-honed protection against the outsourcing of this primordial fantasy. We may have come to believe that our bodies are machines, but our minds, yes: we still like to believe they're gods.